Aurora Muriente Pastrana, who is both a law-school student and adjunct professor in the humanities department at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), had come to the steps of Puerto Rico’s capitol building on April 18 with a group of university students, professors, workers, and activists to raise their voices against the passage of a bill that would eliminate the government-funded Debt Audit Commission, which was created in 2015 to audit the island territory’s $70-plus billion in debt. In solidarity with a group called the Citizen Front for Auditing the Debt, the growing crowd began to stir when representatives of the Citizen Front were not allowed access to the building to observe the bill’s hearings, as is their constitutional right.

Muriente, who is part of a movement that has shut down university operations since March, said the crowd was chanting “We’re Citizens, Not Criminals!” with some urging the police to join them, since their pensions were also threatened by austerity measures. But then, in a poignant echo of the violence that occurred on these same steps in 2010, the demonstrators were, without warning, beset by nightstick-wielding riot police, who fired a barrage of pepper spray at them.

“I was recording what was happening, and the spray reached my hands and arms and I breathed in a lot of it. I had to receive medical assistance,” Muriente said. “Other students and professors were sprayed in the face and hit with billy clubs indiscriminately.”

The return of violence to the capitol steps was a reminder that the US Department of Justice had investigated the Puerto Rico Police Department in 2011 for use of excessive force, which led to a consent decree that placed the department under DOJ supervision. According to Puerto Rico ACLU president William Ramírez, the use of the spray was in violation of the DOJ-enforced agreement with the PRPD. It’s not clear whether the police were emboldened by the recent statement by Attorney General Jeff Sessions that such federal investigations of police abuses would be re-evaluated. At any rate, tensions are rising again in Puerto Rico, now that the Fiscal Control Board—which was created by the US Congress’s PROMESA bill to supervise all government expenditures, and which took power in January—has begun to push for austerity measures, such as a $512 million cut in university funding by the year 2025.

Bernat Tort, who teaches in the philosophy and women’s and gender studies departments at UPR, was hit in the face with pepper spray when he resisted the riot squad’s attempts to push demonstrators away from the building. “We were prepared for the possibility that they might use [pepper spray], but no one was prepared for the stinging pain, all over the body,” said Tort. “I lost my sight for 40 minutes.” Tort, who belongs to a group called Self-Convened Professors in Resistance and Solidarity, feels strongly about supporting an audit of the debt. “The audit would reveal 1) how much of the debt is illegal, 2) who is responsible for putting together the illegal bonds that were sold, and 3) who was involved in the underwriting,” he said.

Both a preliminary report issued last summer by the Debt Audit Commission and a report issued by Saqib Bhatti and Carrie Sloan of the ReFund America Project found that some $36.9 billion of Puerto Rico’s debt was illegal because it either involved “extra-constitutional” debt saddled with predatory interest rates or “toxic” interest-rate swaps. Such findings are most likely behind the rushed bill just passed and signed into law by the current governor, Ricardo Rosselló, to repeal the legislation creating the Debt Audit Commission, as well as passage of a new resolution by Rosselló’s party ally, Senator Larry Seilhamer, requesting that the comptroller general of the United States audit the debt to comply with PROMESA.

While this year’s student movement shares some similarities with the one that took place in 2010, there are important differences, largely having to do with the increased urgency of the island’s fiscal crisis. “Back in 2010, students were fighting against a raise in tuition and an additional charge of $800 annually,” said María de Lourdes Vaello, a first-year law student who was also at the capitol on Tuesday. “The purpose of the university is to provide a high-quality education to the middle and lower classes, but now we’re facing cuts that threaten the very existence of the institution. It’s a much bigger moment.”

Tort feels that the 2010 movement was important because it abandoned the hierarchical structure of the old left in favor of horizontalism, creating a new organizational base. “The difference is, despite the fact that the mobilization is happening over the cuts to the UPR budget, they’re now linking to the general issue of the austerity measures imposed by the Fiscal Oversight and Management Board,” or FOMB, he said. “It’s the base for what we hope to be a national movement against austerity measures in favor of the debt audit, in favor of a moratorium on payment on those portions of the debt that are illegal or illegitimate, and in favor of restructuring the debt so that the payments are linked to investments in economic development and the common good of the country.”

The FOMB’s Spanish sobriquet, “La Junta,” implies dictatorial control, helping to make it an easy target for disenchantment among most Puerto Ricans, who see the board members as outsiders despite the presence of some Puerto Ricans on it. There is popular awareness that board member Carlos García was a past head of Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank and an executive of Banco Santander, which underwrote deals worth up to $61.2 billion of the island’s debt. There is also widespread skepticism about the board’s newly appointed executive director, Ukrainian-American Natalie Jaresko, who will be paid $625,000 a year. She has no experience in the Caribbean, and ethical questions have been raised about her management of a $150 million US-taxpayer-financed investment fund that she ran before becoming Ukraine’s finance minister in 2014.

“Frankly, my opinion is that Puerto Rico right now is not a democracy,” said Vaello. “This is the closest to a dictatorship that we’ve had on this island, and I think it’s being administered behind closed doors, with a lack of transparency. We have to start a series of political discussions and reevaluate what kind of country we want and how are we going to construct it.”

While many progressives in Puerto Rico feel the economic crisis and growing inequality are more pressing than the status issue, the latter is still central to the mainstream political debate. A referendum scheduled for June 11 on the island’s status remains shrouded in controversy. On April 13, the US Justice Department rejected a plebiscite proposal because of unclear wording and omission of the current commonwealth status as an option. So this Tuesday, Governor Rosselló of the statehood party (PNP) delivered an amended version that included the current commonwealth/unincorporated territory option, along with statehood and independence (or “free association”). Neither the commonwealth (PPD) nor independence (PIP) parties support the plebiscite process, and the date has not yet been finalized.

Given the economic and political crises that face Puerto Rico, it’s logical and perhaps inevitable that a movement arising from its 11-campus university system would transcend immediate issues and become the vanguard for a national mobilization. The university—particularly its main campus, in Rio Piedras—is legendary because it was the scene of protests in the 1940s for social and economic justice, in the 1960s and ’70s over the Vietnam War and the Independence movement, and in the 1990s over the US Navy occupation of the offshore island of Vieques. But the university is also a national symbol of culture, tradition, and pride.

“In a colony where the manipulation of information has been the order of the day for 115 years, to have access to a university education has been the most powerful tool of the less-favored sectors,” said Muriente. “It’s been the home of intellectuals, artists, ballet dancers, architects, journalists, anthropologists, and poets. In a country where we don’t have international representation, or even an embassy, it’s a bridge to the rest of the world.”

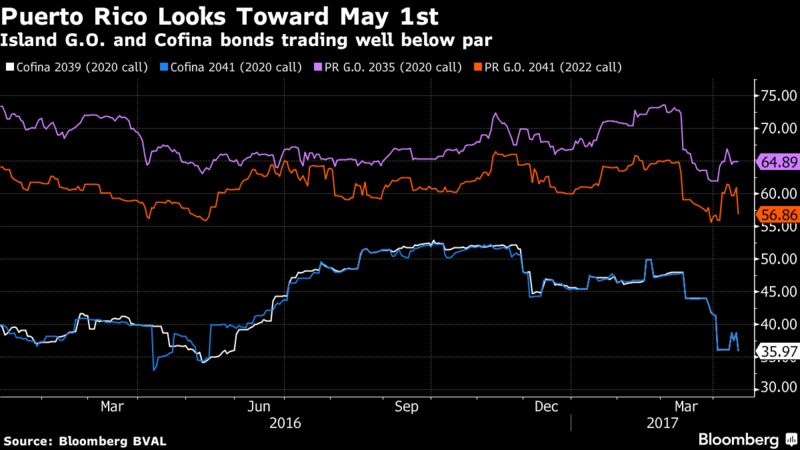

A new deadline for the fiscal crisis is approaching: On May 1, the freeze extended by the PROMESA board on lawsuits over portions of outstanding debt will expire. Of the two debt-settlement mechanisms that PROMESA provides for, the Title III option, which invokes a modified bankruptcy procedure, seems most likely because it provides for an automatic stay on any legal action by creditors. But it also requires the formulation of a debt-restructuring plan. And any such plan would be much more advantageous to the Puerto Rican people if potential illegalities were revealed—as they were in the case of Detroit, which saved millions of dollars.

A report in Reuters last Friday said that lawyers for the Puerto Rico government were drafting an agreement “to avoid invoking bankruptcy protections in the short term.” Yet last week, Puerto Rico’s government dissolved its own debt commission, which had found promising evidence of illegality. In its place, the Senate, claiming the $2 million expense for the debt commission was too costly, passed a resolution requiring the US comptroller general to audit the debt, which the Senate claims is provided for by PROMESA. Opposition party (PDP) Senator Eduardo Bhatia countered by telling El Nuevo Día, “Section 411 of PROMESA does not say that, it does not say that an audit will be done; it says that a report will be made on how the debt is increasing and decreasing, and that it will have some elements. That’s not a debt audit; it’s a debt report.”

On Friday, the Citizen Front called for exploring the possibility of initiating a “citizen’s participatory audit,” a strategy that has been used successfully in Chile, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Romania.

While one deadline looms for the technocrats, politicians, and revolving-door finance executives—who will crunch numbers that could mean life or death for 3.4 million US citizens in Puerto Rico—a movement led, but not limited to, university students will be calling for a different set of priorities, ones that put people first. Because on May 1, students, professors, university workers, labor unions, public-school teachers, religious groups, and those who hold out hope for democracy on the island will be calling for a general strike.

“The UPR strike has managed to create a public conversation, a debate that is obliging everyone to take a side,” said Tort.

Students, workers, and other activists at Puerto Rico’s capitol building, April 18, 2017. (Aurora Muriente Pastrana)

On Tuesday, Rossello said he’s still seeking to craft an agreement before May 1, but he’s waiting for a proposal from creditors, according to a report in

On Tuesday, Rossello said he’s still seeking to craft an agreement before May 1, but he’s waiting for a proposal from creditors, according to a report in