One of the workhorses of Clarke County Hospital, a 25-bed facility in rural Osceola, Iowa, is an unassuming product known as a Mini-Bag.

It is a small, fluid-filled bag used by nurses to dilute drugs, like antibiotics, so that they can be dripped slowly into patients’ veins. The bag’s ease of use has made it popular in small facilities like Clarke County, where the pharmacy is closed on nights and weekends, as well as at nationally known hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic, which uses 34,000 of the bags every month.

“It’s a safe, sterile, stable way to get medications to patients,” said Michele Evink, the pharmacy manager at Clarke County Hospital.

Now, hospital pharmacists across the country are racing to find alternatives — which themselves are becoming scarce — after Hurricane Maria halted production at the factory in Puerto Rico where Baxter, the manufacturer, makes the product.

The bag shortage is the most significant to be directly linked to the effects of the hurricane but others are likely to follow. In addition to creating a humanitarian crisis on the island, the storm knocked out production at the Puerto Rican factories that make vital drugs, medical devices and medical supplies that are used around the world.

Some device and supply companies have already begun limiting shipments of certain items from the island, ranging from mesh for repairing hernias to surgical scalpels and tools used in orthopedic surgery.

On Monday, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, questioned companies’ statements that their plants were back in operation: “We understand that manufacturing is running at minimal levels, and certainly far from full production,” Dr. Gottlieb said in prepared remarks published Monday by the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

He is scheduled to be questioned by the committee on Tuesday. In his prepared statement, Dr. Gottlieb said many plants are running at below 50 percent capacity, “with many firms operating around 20 percent capacity, and some even less. We have found no firm operating above 70 percent of their normal operation.”

In a recent interview, Dr. Gottlieb said he was worried that if conditions don’t improve, more shortages — of both drugs and medical devices — might follow by early next year.

Pharmaceutical products made in Puerto Rico account for nearly 10 percentof all drugs consumed by Americans, and about 80 firms make medical products there, the F.D.A. has said.

“I don’t think we’ve dealt with a situation where we’ve had so many simultaneous impacts to what are very important facilities,” Dr. Gottlieb said. So far, “we have been able to mitigate these issues, but it’s been all hands on deck at the F.D.A., and there’s been close calls.”

Dr. Gottlieb says the F.D.A. is watching the supply of about 30 drugs that are made on the island, in addition to medical devices. Most companies are still running on diesel generators, and manufacturers that have been able to connect to the power grid are still encountering an unpredictable supply of electricity, he said.

Cathy Denning, the senior vice president of sourcing operations at Vizient, which negotiates with medical companies on behalf of its member hospitals, said several device manufacturers, including Medtronic, which makes surgical staples, and Stryker, which makes orthopedic surgery products, were shipping reduced supplies of some products to hospitals because of Hurricane Maria. “We here at Vizient had an ‘aha’ moment when we realized how much manufacturing actually takes place in Puerto Rico,” she said.

Last week, a Johnson & Johnson executive told investors that the company couldn’t rule out “intermittent” shortages of some formulations of its products, although he noted that many were made elsewhere. Johnson & Johnson makes Tylenol and the H.I.V. drug Prezista in Puerto Rico, as well as other products. Soon after the storm, Johnson & Johnson Vision informed customers that a product used in cataract surgery might go into short supply, according to Vizient. A spokesman for Johnson & Johnson said production of the product has resumed, but that it has not yet been shipped from Puerto Rico.

The F.D.A. has been supplying logistical help to companies, providing fuel for the generators and assisting with moving finished products off the island. Dr. Gottlieb said some companies had gotten down to a 24-hour supply of diesel fuel, and representatives for the medical-device industry had said some generators were beginning to break down, requiring emergency repair.

Pharmacists at half a dozen hospitals, from Utah to North Carolina, said in interviews that the fluid bag shortage had had a domino effect, leading to scarcities of a range of products as administrators race to stock up on the supplies they need to keep their hospitals running smoothly. Even products like empty bags and plastic tubing, which are also made by Baxter in Puerto Rico, have been hard to come by, some said.

“With drug shortages, it is often a race to see who can find a supply of the drug on shortage and also any alternatives,” said Philip J. Trapskin, who is the program manager of medication use strategy and innovation at UW Health, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s health system. “We have been able to get what we need to avoid disruptions in patient care, but the mix of products is not ideal and there are no guarantees we will continue to get the supplies we need.”

Baxter recently announced that the F.D.A. had allowed it to import bags from the company’s factories in Ireland and Australia, and said production in Puerto Rico was slowly resuming. The company, which is based in Deerfield, Ill., said it was also helping its employees on the island, including distributing generators and propane-powered cooktops for the workers’ use. “While the storm devastated the island in a day, the recovery will take time,” the company said in a statement.

Baxter did not provide a timeline for when the bags would be back in stock, and pharmacists said they anticipated that the bags might not be available for many more weeks or months. “This is a big deal for hospitals across the country,” said Scott Knoer, the chief pharmacy officer at the Cleveland Clinic. “We’re really still trying to get the information we need to manage it.”

Baxter has been rationing its supply, shipping limited orders of the bags filled with saline and dextrose to hospitals based on a percentage of what the institutions typically use. “We are getting small amounts, but it is nowhere what we need in order to take care of patients,” said Jeff Rosner, who oversees pharmacy contracting and purchasing at the Cleveland Clinic.

The impact has rippled throughout the clinic’s normal operations. Alternatives, such as injecting some drugs into an IV — known as an “IV push” — take more time for nurses, which divert them from attending to other needs. And the method is not appropriate for some drugs. “This has repercussions,” Mr. Knoer said.

The pharmacists said the shortage had not yet affected patient care, although some of the alternatives require that employees learn new systems or adopt complex practices that can introduce human error. If the shortage persists, some said elective procedures, like knee replacements, might be postponed.

It is a predicament that is all too familiar. While Hurricane Maria caused the latest problem, drug shortages have plagued the nation’s hospital system for years. The affected products are typically longstanding staples, like epinephrine or morphine, and are often sterile injectable drugs that sell for low profit margins. In 2014, a shortage of large saline bags, which were manufactured by Baxter and are not currently scarce, led to state and federal investigations into its business practices.

Even the Mini-Bags have previously been in short supply, and pharmacists said shipments of the small bags had been unpredictable before the hurricane.

“It’s like, do we have any great faith this company is going to be able to turn this shortage around, when they haven’t been able to effectively turn around the shortages they had in existence before?” said Debby Cowan, the pharmacy manager at Angel Medical Center, a small hospital in Franklin, in North Carolina’s Smoky Mountains.

Like Dr. Gottlieb, many of the hospital administrators said their eye was on the horizon. With so many drug companies manufacturing products in Puerto Rico, Mr. Rosner said, “I am fearful that this may not be the end of the shortages — it may only be the beginning.”

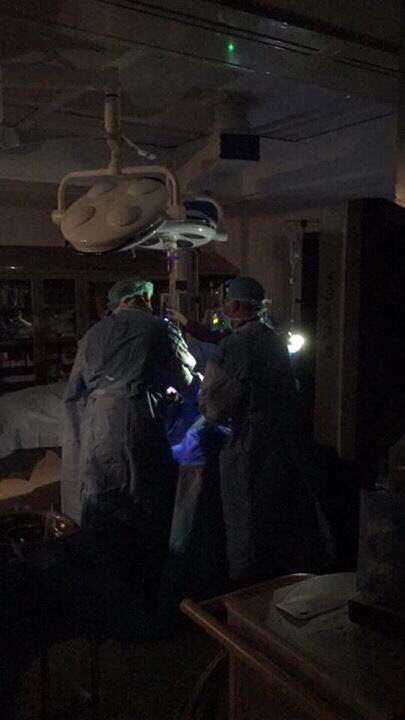

Dr. Michele M. Evink, the pharmacy manager at Clarke County Hospital, holds a Baxter “Mini-Bag,” an item in scarce supply since production in Puerto Rico was hampered by the hurricane.

By

U.S. Hospitals Wrestle With Shortages of Drug Supplies Made in Puerto Rico