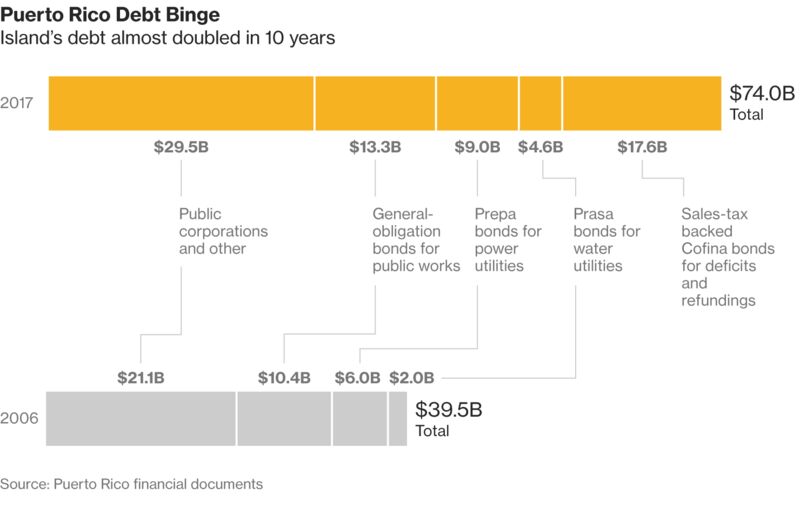

A relatively paltry $16 million has ignited a skirmish among bondholders over who will get paid first and who gets stiffed in Puerto Rico’s $74 billion bankruptcy.

The dispute revolves around interest that’s due June 1 to holders of sales-tax bonds known as Cofinas. Mathematically, the $16 million is barely a rounding error. About $400 million collected from sales taxes is being held in trust -- enough to cover next week’s payment more than 20 times over.

The problem is that Puerto Rico probably won’t have enough cash to pay back all of the $17 billion of Cofinas, so senior and junior holders are concerned that this small payment will set the pattern for who gets reimbursed. What’s more, holders of the island’s general-obligation bonds are watching closely because they’ve made claims on the same stream of revenue. The GO and Cofina groups each contend that they have first priority to be repaid, and say their rivals should get little or nothing because those bonds were issued illegally.

“That’s effectively what it will come down to, GO versus Cofina,” said Mikhail Foux, head of municipal strategy at Barclays Plc. “It’ll probably be the most important lawsuit in this whole Puerto Rico complex, and other municipal bondholders will be watching it.”

Seeking Guidance

Bank of New York Mellon Corp., the Cofina trustee caught in the middle, filed court papers earlier this month asking the judge for guidance on what it should do on June 1, if anything. A hearing is scheduled for May 30 in New York with U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain, and contending parties must file arguments by May 23.

How Did Puerto Rico Go Bankrupt?

(Source: Bloomberg)

The primary dispute is between the two sets of Cofina bondholders, senior and junior, with their payments guaranteed by sales-tax collections. Cofina is the Spanish acronym for the agency that sold the bonds.

The senior group is owed $7.6 billion, with $11 million of interest due on June 1. They’ve argued in a lawsuit against BNY Mellon that they should be paid off in full before the juniors get anything, which could mean holding back the juniors’ $5 million in interest. The subordinated holders naturally disagree, and are pushing to get their share of the June 1 interest and preserve their right to future payouts on their $9.7 billion in debt.

At a May 17 hearing, Swain said her “first choice” would be to delay payment and allow BNY Mellon to hold the money so she could have more time to rule. She scheduled the May 30 session to give all sides a chance to talk her out of ordering a halt to the payment and any related lawsuits.

If the judge blocks the Cofina payment, the seniors could argue that a default has occurred. Under the debt documents, that would give them the right to demand all their money back right away, which would potentially leave little for the juniors.

Alternatively, the judge could rule that Puerto Rico’s fiscal plan -- a blueprint for restructuring the island’s debt by shortchanging investors -- amounts to an event of default. If so, the Title III bankruptcy code gives a 60-day grace period from the date of the default notice for the problem to be remedied. In that case, both senior and subordinated bondholders could still wind up getting their money on June 1, since it would fall within the grace period.

Then there’s the general-obligation bondholders, who own about $13 billion of debt, which the island’s constitution says must be paid before other expenses. They don’t want the Cofinas paid before them. Their lawyers have argued that the Cofina structure is invalid and violates the island’s constitution, because Puerto Rico cannot continue to pay its sales-tax bonds while skipping GO payments, according to a lawsuit the group filed last year against the commonwealth. Lawyers for the GO bondholders say their securities include a claim to any “available resources,” including sales taxes, so they oppose the Cofina claim on the sales-tax revenue.

If their argument prevails, some or all of the Cofina debt could be ruled invalid. A lawyer for the GO bondholders said at the May 17 hearing that he wanted to ensure Swain didn’t rule on the entire Cofina structure’s validity and cast doubt on the GO group’s claim when she rules on the question of the default.

The Cofina holders counter that GO investors are the ones who should be stiffed. Their suit claims that all general-obligation debt issued after 2011 surpassed the constitutional debt limit, rendering it invalid, the group’s lawyer has said. They also say that since the sales-tax revenue is specifically pledged for payment of Cofinas, it doesn’t constitute “available resources” that can be diverted to the general fund.

“There are significant bankruptcy law and constitutional issues that have to be resolved in the fight between GO and Cofina holders,” said Jim Millstein, founder of Millstein & Co., a former adviser to Puerto Rico.

Bank of New York didn’t have a comment beyond its May 15 request for Swain to weigh in on the June 1 payment, said spokeswoman Ligia Braun. Swain is expected to rule on how to proceed on the payment at next week’s hearing, but it’s unclear whether she’ll consider the broader GO-versus-Cofina debate.

The commonwealth’s federal oversight board is considering which class of debt has priority, according to Arthur Gonzalez, a retired U.S. bankruptcy judge who sits on the board.

Both Cofina and the commonwealth have filed for protection from their creditors in a bankruptcy-like process called Title III. BNY Mellon also sent a notice of default to Cofina, stating that the commonwealth’s fiscal plan “undermines” the pledges behind the assets. The New York-based bank acted after weeks of pressure from senior bondowners, who urged the trustee to safeguard their claims.

“If they don’t settle among themselves and with the commonwealth on these interesting questions of constitutional and statutory interpretation, it could ultimately be up to the Supreme Court to decide the issues,” Millstein said. “Which -- unfortunately for all -- will be many moons from now.”

by

and

Puerto Rico Bondholders Deny Legitimacy of Each Other's Debt

No comments:

Post a Comment