Santa Ortolaza lives on a verdant hillside in the mountains of Orocovis, in the center of Puerto Rico. When Hurricane Maria made landfall and the lights went out, she and a neighbor turned on a battery-powered radio and told stories of past hurricanes in the dark. Zinc metal sheets flew outside her windows and wind-blown debris stripped paint from her home’s exterior. She didn’t sleep much that night.

In the morning, she saw the storm had knocked down trees and utility poles, blocking the one road down the mountain. But all her chickens had survived and she was fine, too.

She’d lived through other hurricanes. She knew power might be out for a bit, as in past storms. It’s just how it worked here.

But days turned into weeks, and weeks into months, and still the power didn’t return. Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico’s power grid. About 80 percent of transmission lines were downed, leaving most of Puerto Rico’s 3.3 million people in the dark for months.

Worse, the recovery was moving at a glacial pace.

But even as Puerto Rico’s one utility struggled to turn the lights back on, people on the island and beyond started to talk about rebuilding a better grid. One that could, perhaps, serve as a model for other utilities, states, and countries with aging infrastructure.

The grid

Puerto Rico’s modern grid is owned by the state. It was built starting in the 1940s. First, it used dams for power. Then the government built power plants along the island’s southern coast. The plants used oil from Venezuela, just 500 miles away by an easy sea route, to make energy.

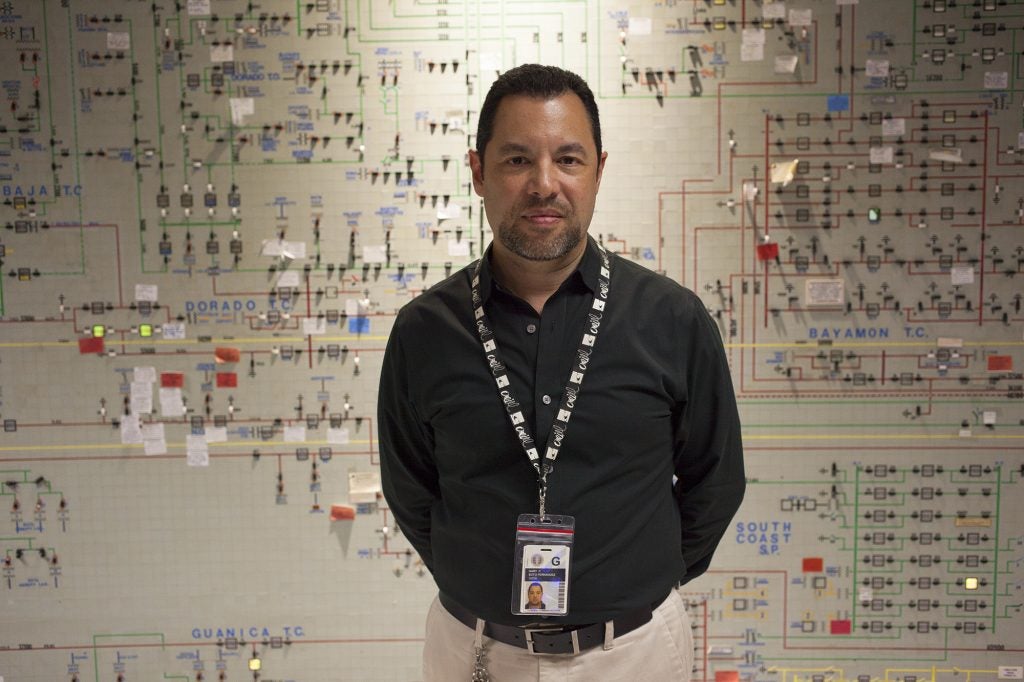

Gary Soto is the operations manager for PREPA. He works to keep the grid operating, but during Hurricane Maria the whole grid went offline – a complete blackout. He says it’s not the first time that happened on the storm-prone island, and not the last, but it’s been a particularly difficult restoration process. Behind him is an analog grid schematic, which hasn’t been updated in decades. (Irina Zhorov/WHYY)

There was a problem, though. Most of the people lived — and still live — in the northern part of the island. Fewer than 40 miles separate the north and south coasts. But the middle, where Ortolaza lives, is crinkled by steep mountains.

The utility strung transmission lines across the mountains. They made power in the south and it traveled by cable to the people in the north.

“We have for electrical purposes, two islands,” said Luis Aviles, who teaches law at the University of Puerto Rico and ran PREPA, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority.

The grid’s very design made the system vulnerable.

But it worked. People had reliable power. So did a rapidly growing manufacturing sector: first garment factories, then pharmaceutical companies, driven by tax incentives from the United States.

It didn’t last. Congress phased out the tax incentives starting in the 1990s. Right after that, the recession hit. Many manufacturers fled to greener tax pastures. PREPA now had fewer customers paying for power, and its finances were being seriously mismanaged, often for political gain.

Today, the power authority is $9 billion in debt.

“And then you have to upkeep that infrastructure, which by now is like 40 years old. And you don’t have revenues to do that,” said Aviles. “It’s a perfect storm. And then we got the hurricanes.”

Maria hits

Maria made landfall as a Category 4. The aging grid couldn’t withstand it. Towers collapsed on the mountaintops where they had precariously perched, cables snapped, transformers blew up. The destruction was vast.

When the winds settled, workers realized there wasn’t enough equipment stockpiled, not enough staff. The mountainous terrain, often accessible only by helicopter, complicated everything. For months, much of the island stayed dark.

On the hurricane’s six-month anniversary, I drove from San Juan about 90 minutes to the center of the island. Once you get off the highway, the roads turn winding, narrow. Barricades squeeze the roads further where mudslides have taken a bite out of the asphalt. At first, the gravity of the destruction is not immediately apparent – your eyes have to adjust to the chaos, as if to darkness. Then you can pick out the cables strewn across the road and hanging, severed, between trees. Poles lean in every direction.

In Puerto Rico, crews are still fixing utility poles and stringing lines in areas that have been without light for nearly nine months. (Irina Zhorov/WHYY)

Santa Ortolaza was still waiting for utility workers to reach her.

A power grid is one of the most complex infrastructure systems in the world, and yet its absence can be felt in the simplest, everyday routines.

“I’ve got all these things I can’t use,” Ortolaza said. The washer, for one, she explained. Standing in a shirt pocked with stains, she listed off the other ways her life had changed in the six months she’s lived without power. She eats less fresh produce because her fridge isn’t cold. She warms water for baths on the stove. She uses solar-powered lawn ornaments to supply light while she bathes. She’s in bed by 7 or 7:30 PM.

“What else am I going to do? There isn’t much,” she said.

An opportunity?

As people like Ortolaza stressed and learned to live without the utility’s power, the rhetoric in the capital and on the mainland turned, in some ways, optimistic.

The destruction of the grid was so immense that some people saw an opportunity.

“The first thought most certainly was, you know, ‘Gosh, here we are unfortunately in a situation where we are as close to a blank-slate situation than we ever thought we actually would be,’” said Julia Hamm, head of the Smart Electric Power Alliance, an organization that promotes renewable energy. For years, her group has led a thought experiment called The 51st State Initiative. It’s not about statehood; rather it’s about dreaming up a better way to manage a power grid without the baggage of existing grids.

A few months after the storm, based on some of the Initiative’s ideas, Julia helped write a report that sketched out how Puerto Rico could build back a better, more resilient grid. One of the major proposals is to add clean energy, like solar and wind, and decentralize the grid.

A way to do that is build smaller grids within the main island grid. Perhaps one for a hospital, one for a small city, a remote town. Each would have its own power source, which could be renewable energy.

When the main grid is working, these smaller grids could connect to it and even supply some power to it. If the grid goes down, the microgrid could disconnect from this larger network and provide power to the people who are within its service area.

As the utility struggled to restore power, some people unknowingly put that plan into action.

Across from Santa Ortolaza’s powerless house, a school is running off its own grid. Solar panels slope towards the sun on the school’s roof, pumping energy into a battery the size of a small refrigerator.

A local company donated the panels, and Sonnen, a German power storage company, provided the batteries to store the energy and power the school.

The school’s principal, Alberto Melendez Castillo, said with the new setup the school will save nearly 30 thousand desperately needed dollars annually. And the school will be prepared for future storms.

“If another event like Maria comes, we’ll have power so the students can have classes with light, can eat fresh food, can drink cold water, cold milk,” Castillo said.

The school serves low-income kids from the mostly rural area. Castillo says he wants it to function as an emergency center for the community, a place where parents can come charge vital equipment and stay connected.

Other small microgrids have popped up or expanded on the island. But if Puerto Rico really wants to build a modern grid, it’ll cost roughly $17 billion.

For now, PREPA’s priority has been turning the lights back on. That means dollars being spent now aren’t going to rebuilding better. They’re remaking the same thing that was there.

“There probably is some money being spent today to fix the current equipment that if we really re-envision Puerto Rico’s power system going forward, that might need to change anyway and be redone to something else,” said Hamm. “But there’s really no other alternative, right?”

Help me.

From the school I wind back down from the mountain. My phone doesn’t work because communications lines are down, too. Miraculously, I don’t get lost, and in 40 minutes I’m in the town of Orocovis. I end up at the house of Maria Esnidel Melendez Colon. Here, it’s easy to see the grid is not some abstract thing.

It’s life.

Colon runs a pair of generators 24 hours per day, and pays $900 a month for fuel. Her mother uses an oxygen machine powered by the generators.

“We never would’ve expected that this would take so long,” she said. It “makes one desperate.”

She goes into her mother’s room. Olga is sitting up in bed, surrounded by hissing medical equipment. She’s almost 97. That means she lived through San Felipe in 1928, the last really big hurricane to hit Puerto Rico, and the electrification of the island.

When we approach her bed, she whispers, “Ayudame.”

Help me.

Nine months after the storm, about 8,000 people are still without power.

Minerva Ortolaza holds a rechargeable bulb her sister, Santa, uses to light her house. The Ortolazas didn't have light for months after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico and they had to change their routines to make do. (Irina Zhorov/WHYY)

Puerto Rico crawls toward full re-electrification

No comments:

Post a Comment